Disciplinary incidents prove the need for a reassessment of the community

- Phoebe Zeidberg

- Oct 6, 2022

- 5 min read

A new Jewish student at Stevenson never thought they would see a phrase calling for the death of Jews presented on their first day at orientation. They called their parents after the incident because they were “questioning if this was the right school for them.”

Stevenson is often required to respond to disciplinary incidents and has to balance the privacy, reputation, and emotions of both victims and perpetrators. During the new-student orientation, the open-ended question “What power do you have to build community?” was posed with students projecting their answers on the board anonymously. One new student chose to respond with a quote alluding to the Holocaust, calling for the death of Jews. The attending teacher, Isabel Aguirre, the Co-Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, mentioned how she could not even contemplate getting this answer from a student: “That was so next level, that was so beyond the range of things that I thought someone would feel appropriate or inclined or even permissible to say,” explaining her shock and confusion. She also mentions how the responses submitted to the student board were never meant to be anonymous. As the leader in the room, many looked to her for an answer. She shut it down immediately, saying, “It was hard for me to finish that presentation and have to address something so horrific and violent and also not be able to provide accountability and hold space for the person who decided that that was the move. It was double hard.”

A new Jewish student, who was present when the incident took place, agreed that they shut down the presentation and the situation was addressed at a later time; however, the moment had lost its impact. A ninth grader agrees, saying, “They handled it, I don’t know if they handled it the best because I don’t think it was really resolved.” Although some teachers addressed the situation in a school-wide assembly, the lack of specificity has left many students unaware of the situation.

During the assembly remark, the Pebble Beach Campus Head, Dan Griffiths, and Dean of Students, Philip Koshi, emphasized that they are intolerant to racism, homophobia, prejudice, and antisemitism. They chose to omit the phrase and its specificity to antisemitism, leading many to apply the school’s intolerance to any prejudiced comment that has been overheard within the Stevenson community in the last couple of weeks. However, Dan Griffiths explains why he chose to omit the phrase: “In this session somebody used really hateful antisemetic language and I usually choose not to share the language that was used because it's usually pretty offensive to say it in public. I don't want to put the students affected by it through that trauma again of hearing this language being used and that’s why you use a broader term;” nonetheless, he recognizes the importance of direct quotes in some situations. In a previous school, he chose to show and use specific, explicit words to explain the gravity of a situation, saying, “Students were being a little bit dismissive about the seriousness of it.”

Coverage of disciplinary events varies case by case and often the student body has a different interpretation of how the events are discussed than the Administration does. Griffiths explains: “You’ve got to balance the opportunity for education. When something happens we can speak about it and share it with the community and explain why it’s unacceptable and why we’re taking it seriously… The decision not to share details often comes down to the nature of the violation of the standards so if it involves other people that have been victims of this behavior quite often to then share the details of that puts them in a very difficult spot.”

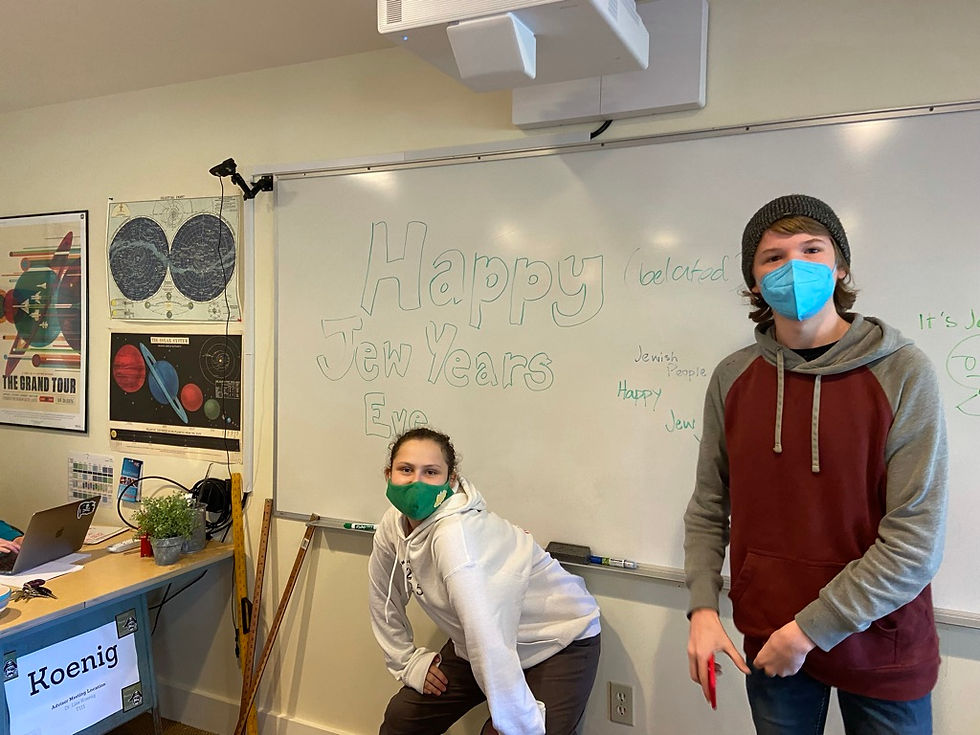

This incident of antisemitism highlights the need for affinity groups. Affinity groups serve as space for those who identify within the group to be able to find comradery and comfort in their peers. The Jewish Student Union did not become an affinity group until this year, after the idea was presented by the former leader of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, Mashadi Matabane, and put into action by Lisa Koenig and the leaders of JSU, Stevie Thomsen and Jake Carlyle. Jacob Rivers, a Co-Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, touches on the importance of this kind of group: “Having it open as a club allows people to come in, but then it gets to the point of more educating people who want to know more about it and who are allies rather than providing the support that is necessary for the identifiers in that group … moving it to an affinity space allows it to focus more on the needs that are not being met for the Jewish community on campus.” Carlyle alludes to these ideas as well, stating “There were no real meetings outside of celebrating our holidays.” This year, they hope to hold events for all of the High Holidays such as Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Passover, and Purim, as well as the quintessential Hanukkah celebration.

The JSU and all Affinity Groups are vital for building community among students. The aforementioned new Jewish student felt as though they could never belong in a room where these statements are said. This is the power the anonymous student had: to make a Jewish student feel as though their community wished they were dead. The affinity group exists to allow students, such as the one mentioned, to feel secure in their Jewish community in Stevenson, especially as a hidden minority. Because Jews can hide behind their whiteness, their identity is often forgotten, allowing incidents of antisemitism to seem like a victimless act. Aguirre comments, “There seems to be a lot of learning that we have to do about antisemitism and the ongoing reality of antisemitism. I think sometimes it is seen as a historical struggle and folks have a hard time understanding that it’s still being perpetuated in very vicious and violent systemic ways.” The overall success of the Jewish community does not undermine the prejudice they face.

Ultimately, this is a story of two new students. One student, a Jew. Another, someone who called for the extermination of Jews. A student population with diversity in thought brings complexity to the community and its values, having the ability to bring people of different backgrounds together to expose them to new ideas and beliefs. This is the job of the teachers: to teach the students what is right and what is wrong. While reading a Holocaust memoir, Maus, Aguirre mentions her student’s lack of knowledge about antisemitism: if there is a void of knowledge in a “classroom of lovely sophomores who are really in it and engaged [with the text], then that’s a helpful reflection in my mind of what is happening in different spaces on our campus.” These differing beliefs and understandings should be met with compassion and education. On the topic of expulsion, Griffiths states: “We always err on the side of trying to find a reason to keep students so that we can help them learn and grow.”

The issue, in this case, is that the community is unable to educate this person directly due to the anonymity of their comment. Because of this, Stevenson was unable to take disciplinary action, leading to the choice to not address it formally with the parents. Griffiths explains: “If we included much bigger community communication around it … the focus would have shifted from what we're trying to achieve getting a new group of students into the school. This is one incident one moment of one student making a really poor choice that we felt was addressed pretty strongly in the moment and after the fact.” Jacob Rivers believes that the actions of this one new student should not reflect the Stevenson community: “The thing that gave me comfort about it is that this came from someone who had been on our campus for hours and so the newest members of our community … do not define what the community is.” Koshi summarizes: “The health of the community is the most important and the student is at the center of that.” Stevenson is still left wondering: “What power do [we] have to build community?”

Comments